A SCALABLE NEAR-LINE STORAGE SOLUTION FOR VERY BIG DATA

Neil Massey1 Jack Leland1 Bryan Lawrence2

1: Centre for Environmental Data Analysis, RAL Space STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, Didcot, UK. and National Centre for Atmospheric Science, UK.

2: Departments of Meteorology and Computer Science, University of Reading, Reading, UK. and National Centre for Atmospheric Science, UK.

This is an expanded version of the paper that appears in Proceedings of the 2023 conference on Big Data from Space, Soille, P., Lumnitz, S. and Albani, S. editor(s), Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, doi:10.2760/46796, JRC135493.

Introduction

The Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) is a division of RAL Space, which itself is a department of the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), a member of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). CEDA is the UK data centre for environmental data and currently has over 50PB of data stored on a range of disk based storage systems. These systems are chosen on cost, power usage and accessibility via a network, and include three different types of POSIX disk and object storage. Tens of PB of additional data are also stored on tape. Each of these systems has different workflows, interfaces and latencies, causing difficulties for users of JASMIN, the data analysis facility hosted and maintained by the Scientific Computing Department (SCD) of STFC, and CEDA.

The Near-Line Data Store (NLDS), developed with ESIWACE2 and other funding, is a multi-tiered storage solution using object storage as a front end to a tape library. Users interact with NLDS via a HTTP API, with a Python library and command-line client provided to support both programmatic and interactive use. Files transferred to NLDS are first written to the object storage, and a backup is made to tape. When the object storage is approaching capacity, a set of policies is interrogated to determine which files will be removed from it. Upon retrieving a file, NLDS may have to first transfer the file from tape to the object storage, if it has been deleted by the policies. This implements a multi-tier of hot (disk), warm (object storage) and cold (tape) storage via a single interface. While systems like this are not novel, NLDS is open source, designed for ease of redeployment elsewhere, and for use from both local storage and remote sites.

NLDS is based around a microservice architecture, with a message exchange brokering communication between the microservices, the HTTP API and the storage solutions. The system is deployed via Kubernetes, with each microservice in its own Docker container, allowing the number of services to be scaled up or down, depending on the current load of NLDS. This provides a scalable, power efficient system while ensuring that no messages between microservices are lost. OAuth is used to authenticate and authorise users via a pluggable authentication layer. The use of object storage as the front end to the tape allows both local and remote cloud-based services to access the data, via a URL, so long as the user has the required credentials.

NLDS is a a scalable solution to storing very large data for many users, with a user-friendly front end that is easily accessed via cloud computing. This paper will detail the design, architecture and deployment of NLDS.

Design Criteria

Before designing and implementing NLDS, an analysis of the previous system, the Joint Data Migration Application (JDMA), was undertaken to determine its successes and shortcomings. These were used to inform the design criteria for NLDS, with the criteria being split into “user criteria” and “system criteria”.

User criteria

User writes files to a single endpoint, agnostic as to whether the file will eventually reside on disk or tape.

User reads files with the same command, from the same endpoint, not knowing whether the file resides on disk or tape.

User interacts with NLDS via a RESTful HTTP API. File URIs are exposed so that they can be read by cloud services.

Command line client and Python libraries available for different levels of user.

Implements CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete), and user interactions are phrased in these terms.

Ingest and retrieval are carried out on behalf of the user, and are asynchronous. The user does not have to maintain a connection for the commands to complete.

System criteria

User interactions are secure and authenticated.

Robust, no user transactions should be lost.

Scalable as number of users and volume of data increases.

No proprietary formats for data.

Flexible and extensible, with the potential to replace several legacy systems.

Portable, able to be installed at other institutions, not just CEDA.

Open Source.

User view and interaction

Users interact with NLDS via a web-server that exposes a RESTful HTTP API (REST). A Python library is available, as well as a command line client, which itself is built upon the Python library. As the interface is a REST API, a user could also form their own, correct, HTTP requests and send them to the server.

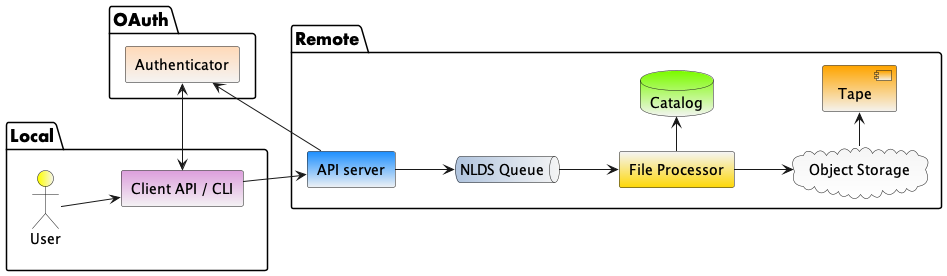

Figure 1 shows the multi-layered architecture of NLDS. The user will only be exposed to the top two layers, being the client API (or command line program) and the API server.

User view of the NLDS system

The first time a user interacts with the NLDS they have to go through the authentication procedure. This uses the OAuth2 password flow to exchange a user’s username and password for a token that is used for subsequent calls to the HTTP API. This token is stored in the user’s home directory and contains a refresh token that can be exchanged for a new token when the existing token expires.

The user has a number of commands available to them which implement the CRUD design requirement and also allows them to query the files they hold on NLDS and the metadata associated with those files. These commands are:

putandputlist.putingests a single file into NLDS, whereasputlistingests multiple files, the paths of which are stored in a plain text file. This corresponds to the Create in CRUD.getandgetlist. Retrieve a single file, or a list of files. This corresponds to the Read in CRUD.delanddellist. Delete a single file, or a list of files. This corresponds to the Delete in CRUD.meta. Update metadata for a collection of files, by adding (or changing) the label or tags.list. Show and search the collections of files that belong to the user.find. Show and search the files that belong to the user. Regular expressions can be used to find file paths, and the collections they belong to.

Implementation details

Overview

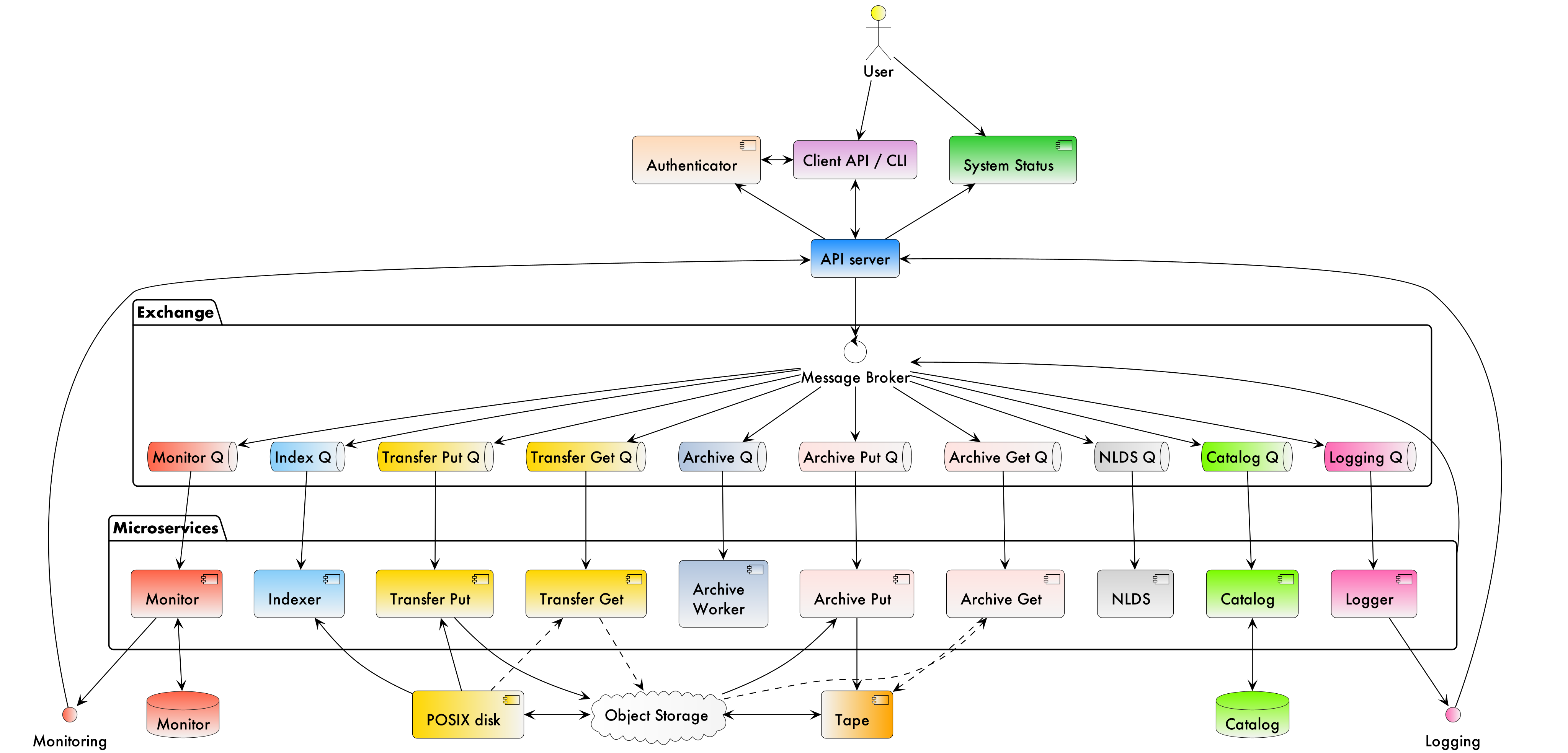

NLDS is built upon a number of free, open-source software technologies in a multi-layered architecture that uses message passing to communicate between the different layers. Figure 2 shows the different layers in the system and the interaction, via the messages, between them.

API server

The NLDS HTTP API is implemented in FastAPI in Python 3, and runs in a Uvicorn ASGI server. FastAPI is a Python framework for developing RESTful APIs and was selected as the framework for NLDS for the following reasons:

Fully supports Python AsyncIO for asynchronously dealing with user requests.

Automatically produces OpenAPI documentation.

Is quick to develop for, fast execution of queries and robust.

Has an easy to understand framework for developing RESTful APIs via the concept of routers.

Integrates well with OAuth2 authentication by allowing routers to be dependent on a function that carries out the authentication of the HTTP request.

NLDS’s API consists of a number of endpoints which accept the standard HTTP methods of GET, PUT, POST and DELETE, with information contained in the header and body of the request. These endpoints, and the expected values in the header and body, are discoverable and documented by automatically generated OpenAPI documentation. In the Python code, each endpoint has a router to deal with the HTTP request. Each router performs authentication, followed by validity checking of the information contained in the header and body and, finally, forms a message that is then dispatched to the message broker.

Authentication and authorisation

As mentioned in Section User view and interaction, NLDS is secured using

the OAuth2 password flow. The authentication layer consists of a plug-in

architecture, with a BaseAuthenticator class, which is purely

abstract. To define an authenticator, the BaseAuthenticator must be

inherited from and three class methods must be overloaded. For the

deployment on JASMIN, a JasminAuthenticator has been written which

contacts a JASMIN accounts service that can generate and authenticate

OAuth2 tokens. Deploying NLDS to a different infrastructure will require

an authenticator for that system to be written.

In addition to the OAuth2 authentication, the object storage that NLDS

writes to and reads from also requires access credentials, in the form

of the access_key and secret_access_key. These are stored in the

user’s NLDS config file, in their home directory and are embedded,

firstly, in the HTTP request sent to the API server, and then in the

message formed and sent to the message broker.

Catalog

When a user PUTs files into NLDS, the files are recorded in a

catalog on their behalf. The user can then list which files they

have in the catalog and also search for files based on regular

expressions. Additionally, users can associate a label and tags,

in the form of key:value pairs, with a collection of files.

NLDS catalog database schema

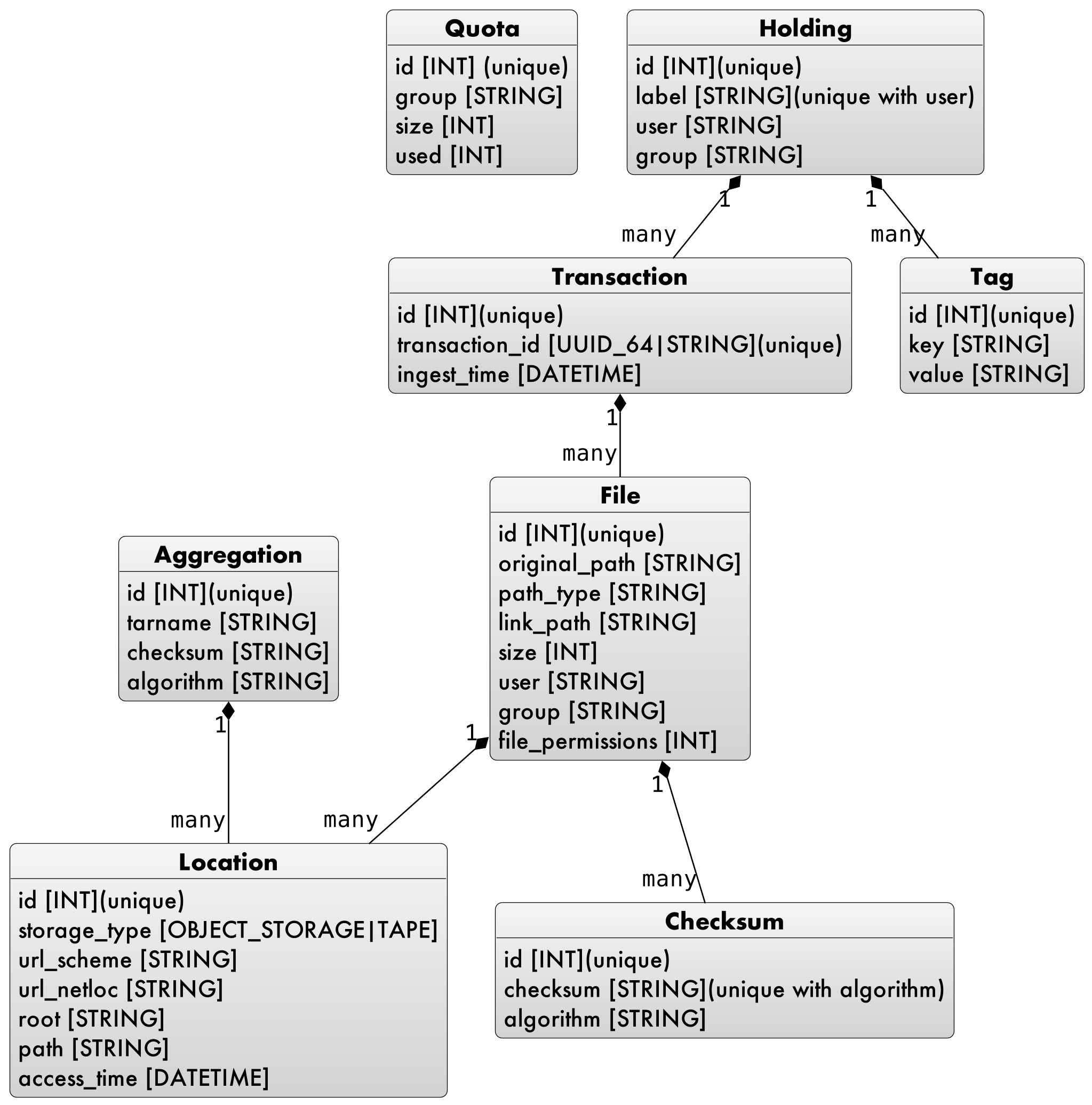

Figure 3 shows the database schema of the catalog. It consists of several tables, each one having a relationship to at least one other table.

Holdings are collections of files, that the user has chosen to

group together and assign a label to that collection. A reason to

collect files might be that they are from the same experiment, or

climate model run, or measuring campaign.

A holding is created when a user PUTs files into NLDS. Users can

give the holding a label but, if they do not, a label

derived from the id of the first transaction will be assigned

instead.

New holdings are created if the label does not already exist and

users can add files to an existing holding by specifying a

label that does exist.

Users can add files into NLDS that already exist in the system, so

long as the original_path is unique within a holding. This

allows users to use NLDS as an iterative backup solution, by PUTting

files with the same original_path into differently labelled

holdings at different times. GETting the files will return the

latest files, while leaving the older files still accessible by

specifying the holding’s label.

Transactions record the user’s action when PUTting a file into

NLDS. Each holding can contain numerous transactions and a

transaction is created every time a user PUTs files into NLDS.

The transaction’s id is a UUID generated on the client when

submitting a request to NLDS. This UUID stays with the transaction

throughout the fulfillment of the request. Requests may be split into

multiple sub-requests, and the UUID is used to group these sub-requests

together upon completion.

The transaction is assigned to a holding based on the label

supplied. If the same label is specified for a number of PUT

actions, then the holding with that label will contain all the

transactions arising from the PUT actions.

Tags can be associated with a holding, in a key:value

format. For example, a series of holding could have tags with

the key as experiment and value as the experiment name or

number. A holding can contain numerous tags, in addition to

label. Tags can be used for searching for files or

holdings with the list and find commands.

File objects record the details of files, including the

original_path of the file, its size and the ownership and

permissions of the file. Users can GET files in a number of

ways, including by using just the original_path where NLDS will

return the most recent file with that path. NLDS supports different

methods of calculating checksums, and so more than one checksum

can be associated with a single file.

Location objects record the actual location of a file. A user does

not care whether a file is on the object storage, or tape, but NLDS

must know so that it can invoke the correct microservice to fetch the

file. The location can have one of three states:

The

fileis held on the object storage only. It will be backed up to the tape storage later.The

fileis held on both the object storage and tape storage. Users can access thefilewithout any staging required by NLDS.The

fileis held on the tape storage only. If a user accesses thefilethen the NLDS will stage it to the object storage, before completing the GET on behalf of the user. Accessing afilethat is stored only on tape will take longer than if it was held on object storage.

Message broker, exchange and queues

NLDS uses RabbitMQ as the message broker to facilitate communication between the API server and the microservices and communication between the microservices themselves. RabbitMQ was chosen for this due to its maturity, flexibility, ease of use and existing experience within the CEDA development team.

RabbitMQ has a publisher-consumer model, where one process will publish a message to be consumed by another process. In NLDS, the API server is the main publisher and the originator of all messages in the RabbitMQ exchange. The NLDS worker is the main consumer and will schedule extra messages depending on the content of the message received. The NLDS worked can be thought of as the “marshall” or “controller”. It knows the message order that tasks have to follow and schedule the next message in the task when a completion message is received from the previous process in the task.

The microservices are the consumers of the messages but they are also publishers, so that they can indicate to the NLDS when the process has finished. This system of completion messages, and the NLDS worker scheduling messages, allows NLDS to be stateless.

NLDS has a RabbitMQ topic exchange with a queue for each microservice. A

topic exchange uses a routing key, and queues can subscribe to accept

messages with a particular key. The routing keys for the messages have

three components: the calling application, the worker to act upon and

the state or command for the worker. These are separated by a dot

(.): application.worker.state

The calling application part of the routing key will remain constant

throughout the operations lifecycle. This allows multiple applications

to use the worker processes without interpreting messages destined for

the other applications. NLDS uses the application key nlds-api.

The worker part of the routing key is just the name of the worker, and

the state or command has, for example, the value of init, start,

completed, etc. When a queue is bound to a topic, it can use a

wildcard in the place of each dot separated part of the routing key. For

example the catalog queue contains the bindings: *.catalog.start and

*.catalog.complete. When a wildcard occurs, any message produced by

the consumer retains the value that the wildcard expanded to, for

example, nlds-api. This is the mechanism that allows generalised

workers to send their output to the originating producer/consumer.

NLDS uses delayed retry queues. If a process fails then it will resubmit the message to the exchange with a delay, so that it can be processed again later. This gives the system the ability to be more fault tolerant by retaining, and automatically retrying, messages until after a problem with the system is fixed. There are a configurable number of retries and the delays increase exponentially for each retry.

The asynchronous nature of the message passing means that it is

unsuitable for user interactions that require an immediate response,

such as the list, meta and find commands. To facilitate

these, remote procedure calls (RPCs) are used. These are non-blocking

due to FastAPI’s use of AsyncIO and so should not have a detrimental

effect on performance.

Microservices

The microservices that NLDS uses to carry out users requests are designed to be robust, minimal and scalable. Each one is designed to perform a minimum number of tasks, related to just one aspect of NLDS. The previous system, JDMA, was somewhat monolithic which, when a part of the system failed, required re-running user tasks from the very beginning. By using microservices, NLDS is interruptible and recoverable. It is also extendable as new microservices can be written to transfer to new storage types, or from different sites, just by defining a routing key and implementing the microservice.

From Figure 2 the microservices are:

NLDS: This is the “NLDS worker” which accepts messages from the API server and co-ordinates message passing between the other microservices. By having a marshalling process, NLDS can remain stateless.

Monitor: The monitor keeps track of the progress of all

transactions, whether they are GET or PUT transactions and updates their

status in a Postgres database via the SQLalchemy

library. Each microservice sends a

message to the monitor at the start and end of the task it is

undertaking. Users can then query the progress of their task using the

stat command, upon which the API server contacts the monitor via a

RPC call, which reports the status of a transaction to the user.

Logger: The logger is distinct from the monitor in that it is concerned with logging the state of the NLDS system, rather than the state of the user transactions in NLDS.

Indexer: This builds lists of files based on the filepath or file

list supplied by the user in a PUT request. This filepath (or multiple

filepaths in a file list) may be a directory, or contain a wildcard. The

indexer expands these to build a list of files that should be PUT into

NLDS. To maintain recoverability, the indexer will split requests into

sub-requests based on number of files and sum of file sizes. When an

index process has reached a (configurable) maximum number of files or

sum of file sizes, it will break from indexing and submit a new message

to the exchange to continue indexing where it left off. The

transaction id is maintained across the sub-requests so that NLDS

can group them together in the cataloging stage. Splitting requests like

this means that the transfer process, and subsequently the archive

process, will have smaller batches of files to transfer and will be more

recoverable from faults.

Transfer: This transfers the files from POSIX disk to object storage, using the standard S3 transport protocol. Currently the min.io Python library is used, but the Amazon botocore library could be substituted.

Archiver: This writes files from object storage to tape by directly streaming, using the xrootd protocol. The tape system used is the Cern Tape Archive (CTA). All files in the object store are written to tape shortly after ingestion.

Catalog: This writes and retrieves the details of a users files to the catalog database. SQLalchemy is used to define the database schemas and carry out the queries.

Management of object storage

It is inevitable that the object storage used by NLDS will become full. To mitigate this, NLDS has a number of policies that determine which files should be deleted from the object storage, while remaining on tape. These policies are expressed in terms of the last access, the file size, any substrings contained in the holding name, and any tags present in the holding.

If a user requests a file that has been deleted from the object storage

then it will be retrieved from tape, staged on the object storage and

then copied to the target directory that the user requested. This is

done by issuing the same command, and the only difference the user will

notice is the extra time the request will take to complete. Requests are

handled asynchronously, so it will not tie up their session by blocking.

They can check the progress of the request using the stat command.

Deployment

NLDS is currently deployed on JASMIN hosted at the STFC Rutherford-Appleton Lab, with users from CEDA, JASMIN and the JASMIN user community conducting beta tests. The deployment uses a mixture of free, open-source technology:

The API server is deployed in a Docker container within a load-balanced Kubernetes orchestration on JASMIN.

The microservices are deployed in Docker containers that are orchestrated by Kubernetes. This allows more instances of a microservice to be “spun-up” when necessary.

The monitor and catalog databases are running on a dedicated, bare metal PostgreSQL server.

The JASMIN accounts authenticator and the RabbitMQ server are running on Virtual Machines (VMs), hosted on JASMIN.

Object storage is provided by DataCore Swarm, but any S3 compatible object storage could be used.

The tape system is the Cern Tape Archive (CTA).

Conclusion

This paper has described a new scalable near-line storage solution that is robust, scalable, extendable, user-friendly and secure. The Near-Line Data Store (NLDS) is currently in beta test, with a roll out to more users of JASMIN planned for later in the year. An extensive user guide and tutorial can be found at nlds-client

Acknowledgement

NLDS was supported through the ESiWACE2 project. The project ESiWACE2 has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 823988.